As the first rays of sunlight touched the Eastern horizon, marking the beginning of another day in 120 C.E., the Roman Empire stood at its zenith, a beacon of power and influence unparalleled in history. During Pax Romana, a period of unprecidented growth, expansion, and cultural exchange, the Roman Empire, sprawled across 1.5 million square miles, housing approximately 130 million people, or 30% of the world’s population. Renowned for their exceptional architectural achievements, from the towering aqueducts that supplied water to their cities to the majestic amphitheaters that hosted gladiatorial games and plays, Romans were also recognized for their formidable military and skilled engineers. They constructed 50,000 miles of road that connected the various cities and provinces of their vast empire, facilitating the free flow of ideas, goods, and people.

Despite the grandeur of the Roman Empire, the tides of history are fickle, showing that no civilization is immune to collapse. Throughout human history, civilizations have risen and fallen, with many ancient cultures lost to the darkness of unknowable history. However, some bygone civilizations, such as Rome, have encoded their fingerprints into the fabric of history for posterity to uncover. The Roman Empire left behind a wealth of well-preserved information, from the artifacts of archaeology to ancient documents, offering countless physical indicators that tell the story of its rise and fall. Intriguingly, one such fingerprint can be found in an unexpected place: the ice of Iceland.

The Romans were masterful miners, skillfully employing hydraulic techniques and tools to extract valuable metals for coinage and essential minerals such as iron, copper, tin, and lead for crafting their tools, sewers, and architectural wonders.

As the Roman Empire ascended to greatness, its industries thrived and expanded, with the mining sector standing out. The remnants of Roman industry drifted on the winds, eventually settling in Iceland’s frozen lands, etching a geological record that mirrored the rise and fall of the empire. In the deeper, older layers, a steady increase in ash deposits hinted at a burgeoning mining industry and an expanding economy. However, in the more recent, shallow layers, a decline in these deposits unveiled a contracting industry and a waning empire - a civilization that once stood tall, now succumbing to the passage of time.

The Roman Empire’s might was sustained by its legionaries, a formidable cohort of soldiers committed to a twenty-five-year tenure without the privilege of marriage. Their discipline and training rendered them an elite force, respected for their tactics and admired for their bravery. Even when facing insurmountable odds, the Roman legionaries held their ground, epitomizing duty, honor, and loyalty in preserving the empire’s peace and justice. The Roman army was structured upon a strict chain of command and a code of conduct that fostered collaboration and efficiency in battle. Its medical corps, complete with surgeons and field hospitals, marked one of the earliest instances of organized military medicine, serving as a blueprint for future armies.

The Roman Empire’s economic prosperity resembled nothing seen before in history, woven from diverse strands, each strand contributing to the richness of the whole. Agriculture and mining formed the empire’s sturdy backbone, supplying sustenance and resources. Military conquests annexed new lands and cultures, expanding Rome’s sphere of influence and trade. A well-constructed infrastructure brilliantly connected the empire’s farthest reaches, facilitating the free flow of goods and ideas.

At the heart of this economic expansion lay a robust currency, providing stability and enabling the sustained growth of the Roman economy. The Roman Empire’s currency, the denarius, was a coin crafted from 3.8 grams of pure silver. Each denarius equaled the daily wage of a skilled craftsman or soldier, and the denarius functioned not only as a medium of exchange but also as a symbol for unity and the empire’s power and authority. A gleaming reminder of Rome’s might and reach.

The Romans were celebrated for their military prowess, social institutions, roads, politics, and, of course, their awe-inspiring architecture and engineering feats. Roman architectural and engineering marvels, defying the ravages of time and weather, continue to astonish us. Even today, two-thousand-year-old aqueducts still supply water to Rome, and numerous ancient Roman buildings remain standing, with some in remarkable condition. The Colosseum, flaunting its intricate arches and vaults, exemplifies the Romans’ expert designs and construction techniques. The Pantheon, one of the best-preserved instances of Roman engineering, stands as a brilliant testament to its creators’ ingenuity and skill.

In stark contrast to the timeless strength of ancient Roman architecture, many contemporary structures crumble and deteriorate within mere decades. Modern concrete is prone to wear and tear, developing cracks and fissures over time. To counter this frailty, modern engineers reinforce concrete with iron rods. Romans, by comparison, possessed both the materials and engineering acumen to construct structures of unmatched resiliency. They harnessed technologies that, from today’s perspective, seem almost miraculous. One such example is their development of self-healing concrete, capable of mending cracks and maintaining structural stability over time. Roman concrete, or opus caementicium, was a durable and long-lasting building material that stands as one of their most significant and underrated achievements.

A recent study1, published in the journal Science Advances by a team of scientists from MIT, has finally uncovered the secret behind the enduring strength of Roman concrete. When examined under a microscope, Roman concrete appears very different from its modern counterpart. For example, it contains small white minerals called lime clasts, which have been absent from concrete for two millennia. These minerals were long thought to result from inferior mixing techniques, but the team at MIT discovered they are actually the key to Roman concrete’s strength and durability. In the experiments, researchers subjected both Roman and modern concrete to stress fractures and then introduced water. Within two weeks, the cracks in the Roman concrete had completely healed, while those in modern concrete remained.

Researchers learned that Roman concrete was created by heating a special kind of limestone, which released carbon dioxide and left behind calcium oxide. This calcium oxide was mixed with volcanic rock and water to create a mortar that hardened over time and became an integral part of the concrete. The lime clasts in the concrete formed a brittle nanoparticle architecture, which, when fractured, became a source of calcium. Mixed with water, the calcium recrystallized into calcium carbonate, filling any nearby cracks. These self-repairing reactions prevented cracks from spreading, serving as the concrete’s own immune system against damage and contributing to the longevity of ancient Roman architecture.

As the Roman Empire fell, the knowledge of how to make self-healing concrete vanished with it. Yet, their architecture remains - its ancient secrets reminding us of their incredible engineering feats. These structures testify to a time when engineering, beauty, and utility were seamlessly intertwined, and buildings were not just functional but also works of science and art. This extraordinary ingenuity is why iconic structures like the aqueducts, the Parthenon, and the Colosseum still stand - two thousand years later and in near-perfect condition. Much of this expertise, sadly, has been lost to history, leaving us to ponder what other advancements vanished with their fall.

The Romans were not only master builders but also master innovators, scientists, philosophers, and economists. Beyond self-healing concrete, they harnessed central heating, advanced mining techniques, fostered international trade, and enabled upward social mobility. The Romans drove the progress of modern philosophy, science, technology, architecture, law, warfare, and finance, forming the bedrock for present-day civilization. The truly captivating mystery is not how they constructed 50,000 miles of road or erected awe-inspiring monuments like the Colosseum, nor how they revolutionized the world by transcending its primitive origins and laying the groundwork for modern civilization, but rather: why did they stop?

THE COLLAPSE OF COMPLEX SOCIETIES

American anthropologist and historian Dr. Joseph Tainter2 argues that increasing complexity has been the leading driver for the collapse of ancient civilizations. To better understand his thesis, we must define these terms:

-

Complex society. A complex society is one with many moving parts, distinct occupations, and institutions.3 Hunter-gatherer societies, for example, had only a few dozen occupational roles and poorly organized institutions, in contrast to the large number of distinct twenty-first century occupations and well-organized institutions. In the hunter gatherer age, every profession was centered around food and survival. Our current society. In contrast, our contemporary society thrives on intricate complexity, with a remarkable degree of specialization in tasks that our ancestors could never have imagined.

-

Collapse. Collapse is defined as the rapid simplification of society.4 Although a collapse may take several centuries to unfold, it is still considered rapid when compared to the time it took to build the civilization. In the aftermath of the disintegration of a complex, intricately interwoven society teeming with a myriad of professions and well-orchestrated institutions, there emerges a landscape of simple, disjointed communities with few distinct occupations, where the majority toil as illiterate farmers, unable to pen a word or decipher a script. The few surviving institutions are mere shadows of their former selves, disorganized and bereft of purpose. As civilizations crumble, we are left to mourn the loss of their knowledge, culture, literature, and technological prowess.

In our pursuit to unravel the complexities of the rise and fall of great and powerful civilizations, we must also recognize the distinctions between society, empire, and civilization themselves.

A society is made up of individuals bound together by shared culture, values, norms, and institutions. It can span from tight-knit village communities to nation-states to entire civilizations.

An empire is a political entity encompassing multiple societies and territories, often governed by a single authority such as an emperor or monarchy. Possessing a centralized government, an empire exercises control over a diverse population, frequently through the force of its formidable military.

Lastly, a civilization is a complex culture hallmarked by refined forms of government, art, religion, and technology. Civilizations can extend across numerous societies and territories, either as the offspring of an empire or blossoming independently. Society and civilization are often used interchangeably.

As society expands, complexity inevitably arises from both innovations and the inherent challenges accompanying growth. We, the inhabitants of the twenty-first-century society, dwell within the most intricate society humanity has ever known, one that requires tremendous resources5 in complex and expensive solutions to maintain its existence. And with complexity comes an array of problems, each more formidable and costly to resolve than the last.

Take Manhattan’s burgeoning population, for instance. As the number of residents increases, housing becomes an urgent concern. The solution? Constructing towering skyscrapers. Although these awe-inspiring structures may solve one problem, they introduce another layer of complexity to society, giving rise to new issues such as air traffic safety concerns and added strain on existing infrastructure like power grids and water supplies.

Similarly, the advent of highways and automobiles revolutionized transportation and infrastructure, addressing numerous societal problems. Yet, this progress spawned new challenges, including traffic accidents and environmental pollution. We introduced skyscrapers, highways, and automobiles to tackle our challenges and advance as a society. This progress inevitably bred new difficulties. In short, remedying one issue - whether it’s housing a growing population or enhancing our mobility - often demands heightened complexity, investment, and resources, thereby creating an unending cycle of escalating complexity.

Each solution to a problem births new issues, perpetuating an endless cycle of problems and solutions. Faced with this pattern, society may either reach a “singularity crisis” or indefinitely progress and evolve towards a post-scarcity world6. The choice we make will ultimately shape the future of our ever-evolving society.

-

The Singularity Crisis: The singularity crisis represents a state of irreversible societal decline triggered by the exhaustion of a society’s resources. Civilizations naturally oscillate between progress and decline, but when resources are depleted, reversing this decline becomes arduous, causing society to drift toward ever-simpler states. This crisis emerges when sustaining a complex society becomes unaffordable, or when new problems are too costly to solve, leading to resource exhaustion. In such a crisis, the challenges of maintaining complexity outstrip available resources, prompting a marked decline in social and economic structures - a devolution of society. The singularity crisis is the point of no return, when society can no longer reverse its decline and collapse becomes inevitable.

-

Indefinite Progress: Alternatively, if a society successfully navigates the risks of complexity, it can develop into a post-scarcity society, transcending the singularity crisis. In this hypothetical economic landscape, goods are abundant, and labor demands are minimal, as society becomes automated through robotics and AI systems. In a post-scarcity society, the marginal cost of energy approaches zero, and humanity evolves into a species liberated from the shackles of wage slavery, thriving in a world of limitless potential.

Societies undergo cycles of growth and decline, ebbing and flowing between complexity and simplicity across centuries or even millennia. Ultimately, they gravitate toward one of two outcomes: an irreversible decline culminating in collapse or an evolution into a post-scarcity society.

Dr. Tainter posits that increasing complexity will inevitably reach a point of diminishing returns. As complexity often comes with a high cost and generates new problems, progress may eventually overwhelm societies financially, leading them to crumble under the weight of their own advancements.

In this chapter, we explore the current state of our global civilization, assessing whether we are progressing or regressing. We also consider if our development has been hindered by the very progress that has brought us this far.

Before delving deeper into this saga, it is vital to clarify what we mean by “collapse,” a term tainted by popular fiction and Hollywood films. We must separate our understanding of society’s potential fate from cultural influences and focus on the authentic nature of decline and collapse.

A collapse is not an abrupt, catastrophic event but rather a slow, steady erosion unfolding over time, often spanning centuries. It is marked by a gradual decline in institutions, living standards, and population, coupled with rising poverty and civil unrest. Contrary to popular culture’s depiction of collapse as a violent event with riots, looting, burning buildings, and destruction, these chaos points are not defining characteristics of a genuine collapse.

A collapsing society, like a slowly eroding bedrock, undergoes subtle changes that, over time, can lead to devastating losses in population, living standards, knowledge, technology, literature, culture, and morals. However, since civilizational decline can be an almost geologically slow process, those living within a collapsing society may be entirely oblivious to their plight.

As for the state of our current civilization, the truth is that the gentle threads of the apocalypse may already be taut, but the signs of an impending collapse are often imperceptible or easy to dismiss. If our global civilization were to experience a fate similar to the Roman Empire, it would not be marked by earth-shattering events but rather by the continuation of everyday life. If we were in decline, we would experience nothing out of the ordinary. We would experience precisely what we experience today.

POVERTY AND DEPOPULATION

History shows us that the decline of civilizations unfolds as a gradual process spanning centuries, not just mere decades. Each generation might only witness subtle changes, such as marginal declines in the quality of life, less nutritious food, reduced leisure time, and fewer children. Over time, however, these micro shifts accumulate, causing society to devolve from a complex, interconnected entity with diverse occupations, developed infrastructure, and large, well-organized institutions to small, simple, and poorly connected communities of illiterate farmers and drastically reduced populations. Consider the 1950s, when a young couple with two to four children could afford a comfortable home, a reliable vehicle, a family vacation once per year, and even savings, on a single income without any debt. Now, despite decades of economic and technological advancement, the middle class struggles to attain even a modest standard of living with dual incomes and a heavy debt load. The median household income has not kept pace with inflation, and the cost of living has dramatically increased. Across generations, inflation breeds poverty and erodes our ability to maintain institutions and address increasingly complex challenges. As poverty spreads, flourishing turns to withering, and childbearing gives way to mere survival and toil.

While overpopulation may strain resources and the environment, transcending the singularity crisis and reaching a post-scarcity society requires investment and growth rather than consumption and conservation. Overpopulation may bring challenges, but unlike underpopulation, it does not pose a direct existential threat to humanity. A declining population is not just a severe sign of societal degradation, but also a factor that exacerbates further decline. The slow implosion of an economy creates a society where its inhabitants necessarily grow increasingly preoccupied with compensating for inflation, fighting wars, or repairing damage, rather than focusing on growth and development. Societies collapse when its inhabitants prioritize survival over forming partnerships and building families. In other words, societies collapse when they stop having children.

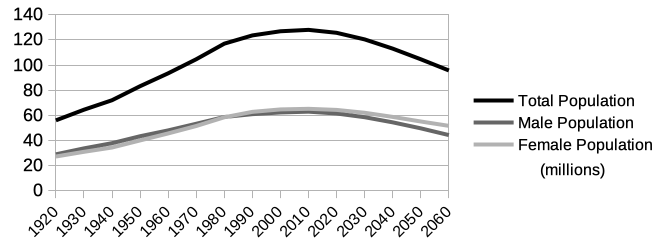

The United Nations reports a declining global birth rate since the 1960s, projected to decrease further in the coming decades. In 2019, the average fertility rate was 2.5 children per woman, expected to drop to 2.2 by 2050. Some countries, including Japan, China, the USA, Italy, Spain, and Greece, already have birth rates below the replacement level, indicating a widespread trend of depopulation that threatens the collapse of economies, erosion of cultural heritage, and the inability of society to sustain itself.

China faces challenges such as an aging population and energy and food shortages, all contributing to significant demographic decline. In the coming decades, China may experience a higher percentage of population loss than Europe did during the Black Death of the 1300s. Depopulation is a far greater threat to civilization than overpopulation, and the only reason the world population is not yet plummeting is that people are living longer than ever before.

Global depopulation, a stark indicator of societal decline, could potentially lead to the collapse of civilization. With a birth rate 40% below the replacement level and adult diapers outselling baby diapers since 2012, Japan highlights the compounding effects of depopulation. Japan’s population decreased by 644,000 in 2021 alone, and it projects a 30% decline to 88 million by 2065. Japan’s birth rate has been alarmingly low, prompting former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe to declare that the country is on the brink of being unable to function as a society. According to official data, Japan’s population peaked at 128 million in 2017 and is now estimated to drop to under 53 million by the end of the century. The aging population of Japan, with the second-highest percentage of people 65 years and older, warns of an alarming global trend.

THE 1970S: A TURNING POINT

Half a millennium ago, the Age of Discovery and the Age of Enlightenment heralded the dawn of modern civilization. Fast forward to today, and humanity has accumulated vast knowledge, unprecedented wealth, and technology that verges on divine. We have become a global, spacefaring civilization that reaches for the stars.

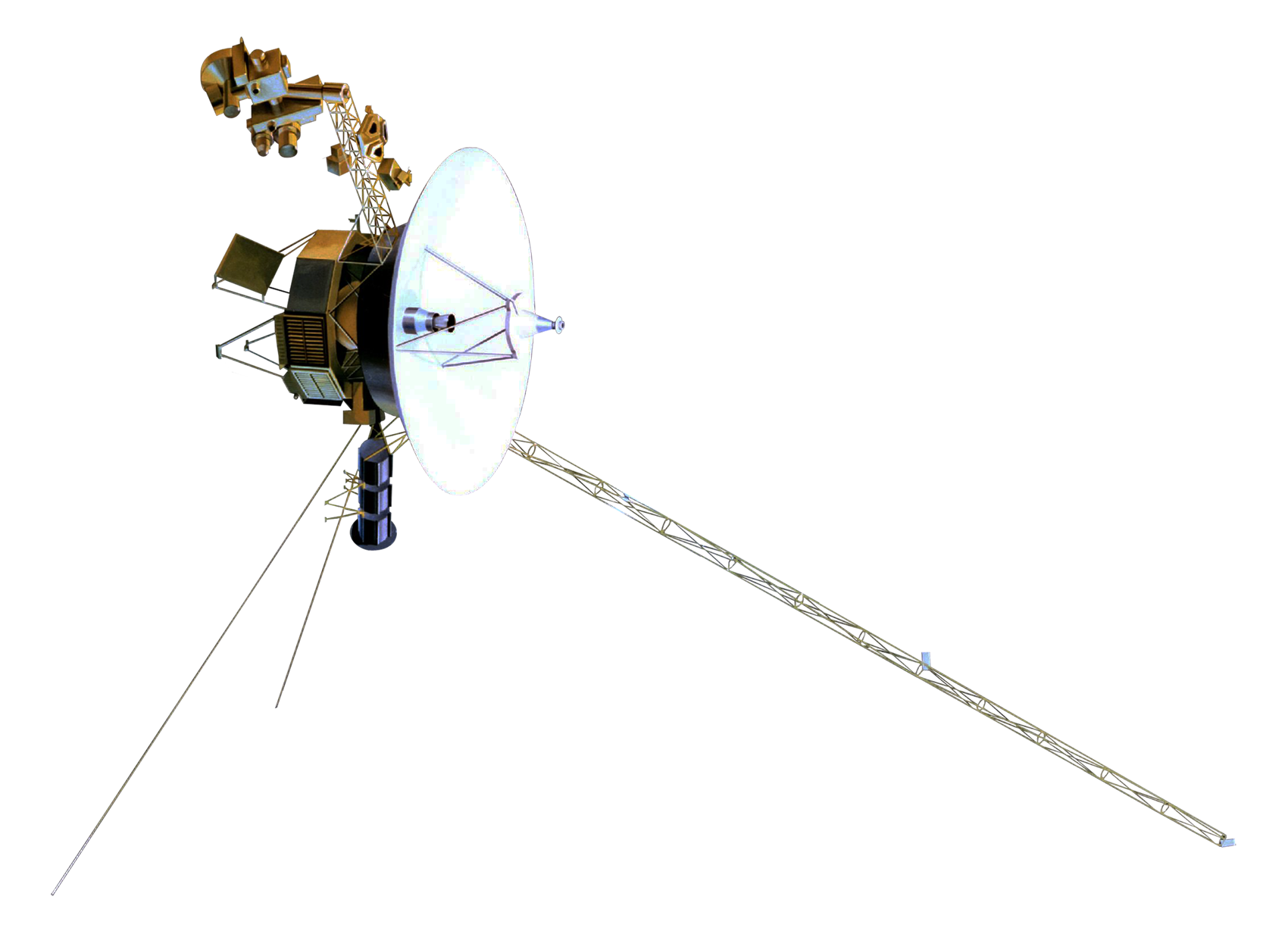

The 1970s proved to be a crucible of innovation, birthing the personal computer, mobile phone, internet, genetic engineering, renewable energy, and video games. Yet, among these milestones, NASA’s Voyager program, launched in 1977, stands out as an awe-inspiring symbol of our collective spirit. This cosmic endeavor transcended technology; it was a testament to our values, pride, and aspirations. The moment Voyager 1 and 2 soared into the heavens marked a defining chapter in the annals of human history.

So, what sets the Voyager program apart? These probes signify humanity’s foray into the great unknown, exemplifying our engineering ingenuity and insatiable thirst for knowledge. With a mission transcending mere scientific exploration, the Voyager program sought to deepen our understanding of the cosmos. Destined for the heart of the Milky Way, Voyager 1 and 2 bore inscriptions, images, and recordings emblematic of the human species, its knowledge, and culture.

A message in a bottle, adrift in the cosmic ocean, the Voyager program is a vessel bearing a testament to Earth’s past, our achievements, and our indomitable spirit. As the probes traverse the infinite, they serve as an eternal monument, a testament to the legacy of humankind. Carl Sagan on the contents of the message:

As each Voyager left Earth for the planets and the stars, it carried with it a golden phonograph record encased in a golden, mirrored jacket containing, among other things: greetings in 59 human languages and one whale language; a 12-minute sound essay including a kiss, a baby’s cry, and an EEG record of the meditations of a young woman in love; 116 encoded pictures, on our science, our civilization, and ourselves: and 90 minutes of the Earth’s greatest hits - Eastern and Western, classical and folk, including a Navajo night chant, a Japanese shakuhachi piece, a Pygmy girl’s initiation song, a Peruvian wedding song, a 3,000-year-old composition for the ch’in called ‘Flowing Streams,’ Bach, Beethoven, Mozart, Stravinsky, Louis Armstrong, Blind Willie Johnson, and Chuck Berry’s ‘Johnny B. Goode.’

- Carl Sagan

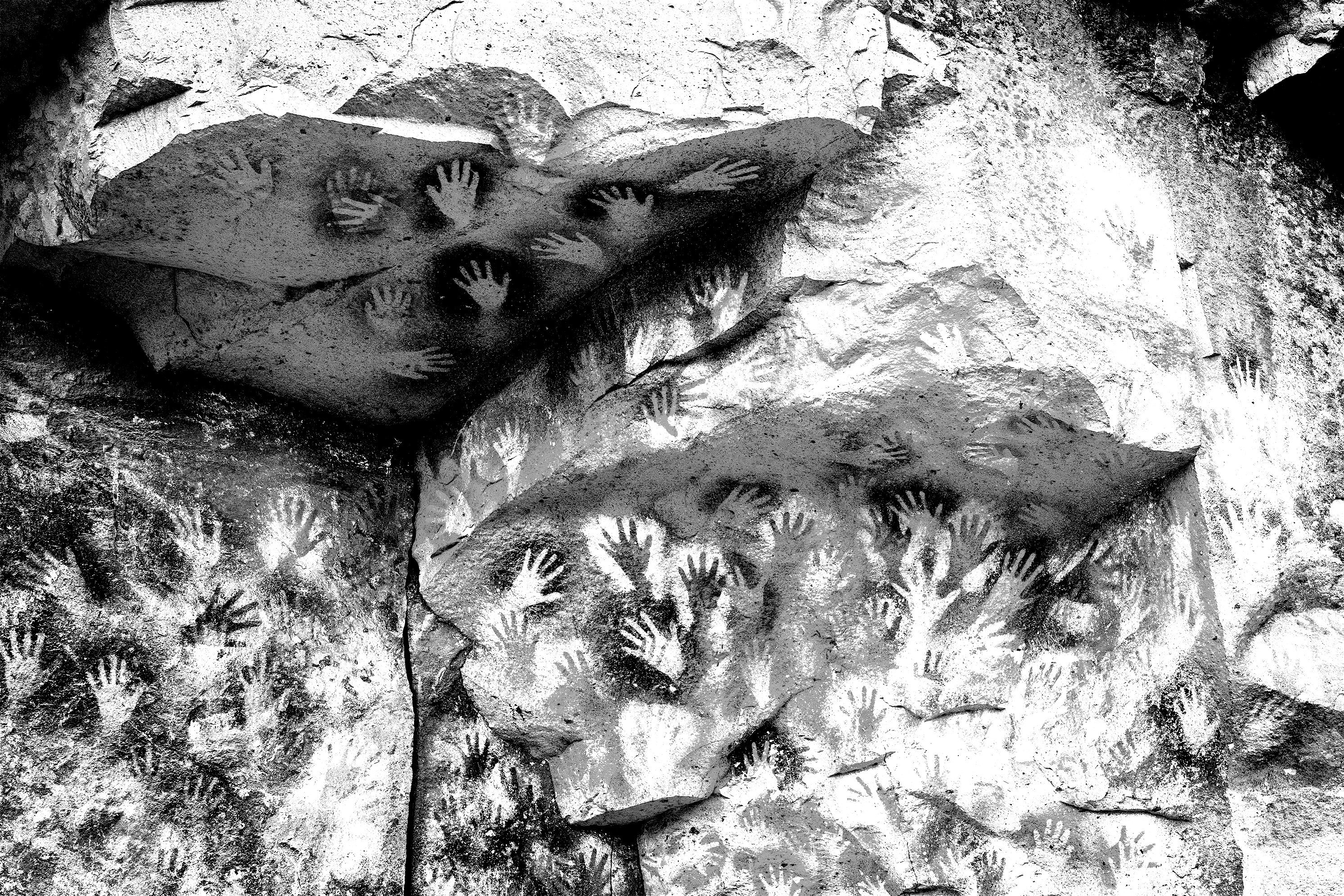

Our generation is not unique. Since the dawn of recorded time, humans have sought to communication beyond our present realm. Some 10,000 years ago, deep within the Patagonian caves of Argentina, a group of hunter-gatherers left an indelible mark on history. The cave walls showcase 829 handprints in black, white, and red - created by pressing hands against the rock and blowing pigment through a bone tube. The majority of the handprints were made by men, with one bearing six fingers, and all but 31 of them are left hands.

In Sapiens, historian Yuval Noah Harari poignantly describes these handprints, writing, “It looks as if these long-dead hands are reaching out towards us from within the rock. This is one of the most moving relics of the ancient forager world - but no one knows what it means.” Though their meaning remains elusive, we can envision them as a powerful proclamation: I was here, I existed. This enduring sentiment uncovers the timeless human desire to make a mark and forge a lasting legacy.

Handprints represent the oldest shared tradition in human history. Perched atop a Tibetan plateau 13,000 feet above sea level, the most ancient handprints ever discovered date back an astonishing 200,000 years. These marks narrate the story of two teenagers who deliberately left hand- and footprints on a travertine boulder, forever united by a simple yet profound gesture. Some scientists interpret this event as a deliberate artistic act, making it the earliest currently known example of parietal art in the world7.

The Voyager spacecraft, soaring through the cosmos, serve as humanity’s earliest cosmic handprints - testaments to our existence and ambition, etched across time and space. These declarations echo the ancient handprints and the architectural wonders of lost civilizations. These “handprints” celebrate our indomitable spirit and determination to leave a mark on the world. They are not merely monuments to our achievements, but also markers of our passage through history, bearing the unique fingerprints of the civilizations that created them.

As the Voyager spacecraft sail across the cosmic ocean for billions of years, they carry the human story, a timeless vessel adrift in the vast expanse of the universe. These beacons of hope offer the promise that one day, someone, somewhere, will uncover the tale of who we were. The Voyager project exemplifies not just our relentless pursuit of knowledge but also our desire for connection, mirroring the aspirations and hope that defines us as a species.

This is what sets the 1970s apart. The 1970s were a momentous era of self-reflection when humanity paused to appreciate its accomplishments and dared to dream of its future and the legacy it would leave behind. This spirit of the era manifested itself in the launch of the Voyager probes, one of the most impressive and symbolically powerful monuments ever created, into the heavens.

The 1970s shone like a golden age, a radiant epoch of unprecedented prosperity, akin to the zenith of the Roman Empire in the second century. The decade brimmed with boundless possibilities, as humanity soared to the pinnacle of its achievements. Yet, beneath the dazzling veneer, dark shadows brewed on the horizon, heralding the onset of societal and economic decay.

Indeed, in the past half-century, our technological and economic advancements have been nothing short of awe-inspiring. The invention of the silicon chip, the development of CRISPR technology, the construction of CERN’s Large Hadron Collider, the discovery of the Higgs boson, and the launch of the James Webb Space Telescope are just a few achievements that have revolutionized our world and catapulted us toward an era of unprecedented progress. Through our tireless efforts and dedication, it seems we have now reached the pinnacle of human achievement, surpassing even the extraordinary heights attained in the 1970s.

As our journey forward continues, a nearly undetectable yet menacing phantom of societal decay looms. This decline is not a simplistic portrait, but rather a multifaceted mosaic with intricate and interconnected pieces. The ever-widening chasm between the rich and the poor, the despoilment of our natural environment, and the growing polarization and dysfunction in politics are often viewed as evidence of decline. Yet, beneath these conspicuous markers lurks an even darker metamorphosis - a deep-rooted transformation that festers within a society spiraling downward.

In the dark recesses of societal decline lies a symbiotic relationship with economic decay. As societies falter, currencies devalue, and financial systems crumble, the vicious cycle of decline intensifies. This deterioration births a seismic societal shift, marked by the harbingers of decline: rampant inflation, collapsing institutions, escalating poverty, eroding living standards, civil unrest, growing apathy toward the future, and dwindling populations.

In a decline’s early throes, these ominous signs may not hinder economic and technological progress. Even as the seeds of decay are sown, progress can persist unfettered for decades, even centuries. It is only when the roots of decline have entrenched themselves within the fabric of society, squeezing over extended periods, that their impact becomes truly destructive.

FROM SILVER TO SHADOWS

In the shadows of antiquity, the Roman Empire waged a relentless series of devastating wars, staining its legacy with blood and destruction. Among these brutal conflicts, the Roman Civil War (49-45 BCE) seared itself into history as a particularly vicious chapter, extinguishing the Roman Republic with its appalling toll of 300,000 souls. The Jewish-Roman War (66-73 CE) brought about the horrifying demise of over 1.1 million Jews and 100,000 Romans, culminating in the obliteration of Jerusalem’s Second Temple. The Punic Wars (264-146 BCE) between Rome and Carthage, too, were among the deadliest of ancient times, leaving an estimated million dead in their wake. The Gothic Wars (376-382 CE) and the Roman-Persian Wars (92 BCE-627 CE) saw a combined death toll of over 2 million, casting a somber veil over the empire’s turbulent history.

To maintain its vast territory and prevail in countless battles, the Roman Empire forged a formidable, ever-expanding military force. The staggering cost of such an army, coupled with the constant need for a military presence along its borders, insidiously drained the empire’s treasury over the centuries. A striking 90% of the government’s expenses were devoted to its military, driving the empire to continuously expand its capabilities - and its costs. Eventually, the Romans stretched their territory and military ambitions beyond their socioeconomic limits, triggering repeated fiscal crises and creating a vicious cycle of costs and strain.

In 64 CE, Rome faced yet another calamity when the Great Fire ravaged the city for six interminable days and seven nights. The fire’s origins lay in the densely populated merchant shops near the chariot stadium, and from there, rapidly engulfed the surrounding area. Historians still debate the extent of the damage, but all agree that the death toll numbered in the thousands. Nero, emperor at the time, vowed to rebuild Rome and instituted reforms aimed at improving the city. Among these were building codes mandating use of fire-resistant materials and the widening of Rome’s narrow streets. In a way, the Rome’s Great Fire planted the seed for the blueprint of modern city planning.

Nero’s grand rebuilding ventures demanded immense labor, materials, and funds. To finance these expenses, Nero debased the Roman currency by reducing the silver content in the denarius. Rebuilding efforts also diverted resources from other regions of the empire, contributing to an overall decline in political and economic stability, as resources were stretched thin and other areas were neglected.

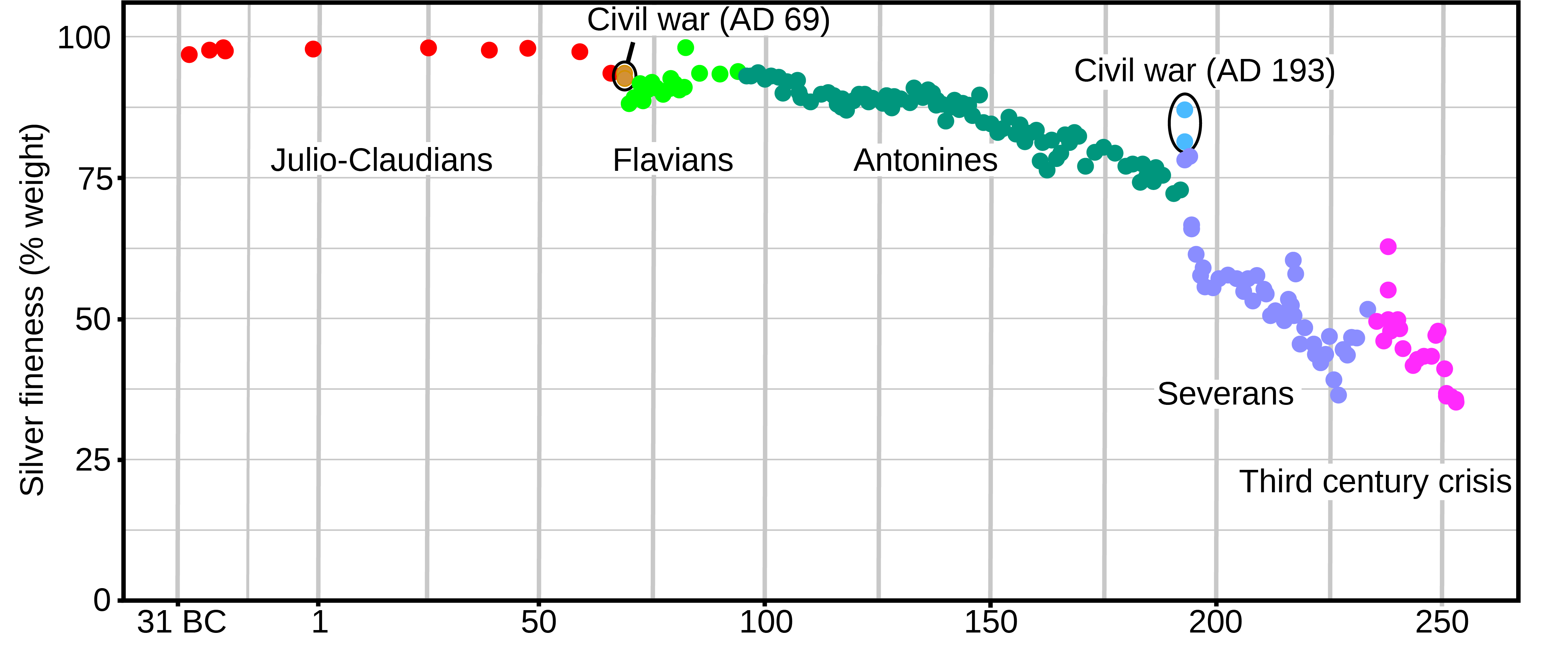

To consolidate their rule, secure military dominance, and recover from the devastation wrought by the Great Fire and wars, Roman leaders continued to debase the denarius. This short-term strategy had long-term consequences. During the reign of Emperor Marcus Aurelius (161—180 CE), the denarius contained a mere 75% silver, a steep drop from its original purity. By the time of Emperor Gallienus (253-268 CE), the silver content had plummeted to a paltry 0.5%. This debasement, designed to mint more coins with the same face value, triggered an irreversible downward spiral of the Roman Empire, poisoning the economy and hastening its decline. The denarius, once a proud symbol of Roman wealth and power, was reduced to a mere shadow of its former self, foreshadowing the eventual fall of an empire that had once soared to the pinnacle of the ancient world.

Starting with Nero in 64 CE, the fifth and final emperor of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, the Romans began to debase the denarius. Note that by the close of the third century CE, the denarius had become nearly bereft of silver. The diagram concludes at 250 CE, but the denarius would be entirely stripped of its silver within two decades.

Money, the lifeblood of society, pulses through its veins, propelling progress by orchestrating collective efforts and allocating resources. But, like toxins in our bloodstream, toxic money - devalued currency that can be easily and inexpensively issued - coursing through society can herald its decline. A malfunctioning financial system not only stifles progress and coordination but also amplifies the difficulty of reversing societal decay.

Beneath the fabric of every civilization lies its money - the enigmatic bedrock that allows a civilization to rise and whose elusive definition has beguiled humanity for millennia. To unravel the perils of currency devaluation, we must first decipher money itself. Robert Breedlove, the charismatic host of the aptly named show What is Money?, passionately explores this age-old question, dubbing it the defining question of our century.

Breedlove astutely observes that our perception of money mirrors our psyche, exposing our innermost selves and values. For some, money is a means to an end, securing a future for their family or a desired lifestyle, while visionaries like Michael Saylor famously portray money as a form of energy.

Money, a silent storyteller, chronicles the ebb and flow of human energy, aspirations, and accomplishments. Each transaction adds a new phrase to the ongoing saga of humankind’s endeavors. Money’s definitions vary. Some are imaginative; others are pragmatic, and some describe it as a collective hallucination, a term I find misleading. More accurately, money is a shared memory of good and bad deeds in society, and a self-reinforcing social institution. Put simply, money is money because people believe it to be so.8

Personally, I join countless others in perceiving money as a proxy for time. This simple yet profound notion posits that money serves as a battery for time. As you sell your time for money, you store your time in a token that can be transported across space. As we exchange these time tokens for goods and services at a later date, we trade slivers of our finite lives. I see money this way because I have difficulties managing my time and desire above all else to have more time.

Money’s story, however, extends beyond the individual. It forms the bedrock upon which civilizations rise and fall. It is the lifeblood coursing through society’s veins, weaving the magic of collaboration across continents and generations. Money orchestrates the intricate dance of civilization, coordinating its workforce and resources. As the conductor of the symphony of human progress, money is our most vital instrument for ensuring the health and advancement of society.

As we recognize money’s vital role in society, we come to see currency devaluation as more than just the theft of an individual’s time. It ominously erodes the very foundations of civilization, leaving us with a weakened tool for coordination and collaboration. In this way, currency devaluation sets the stage for a harrowing societal decline.

A debilitated currency falters in comparison to a robust one, much like a plastic hammer pales against hardened steel. The denarius, once stripped of silver, lost its effectiveness compared to when it boasted a near one hundred percent silver content.

Currency devaluation sparks a downward spiral of the economy, morals, and institutions, that, once unleashed, threaten to ossify and send society toward collapse. Historically, monetary devaluation has never self-terminated, and the responsible entity - typically the state - has never voluntarily ceased this destructive process.

Throughout the ages, societies have oscillated between progress and decline, but decline need not inevitably culminate in collapse. Often, the pendulum swings back, ushering in a new era of progress. Yet, the profound danger of societal decline lies in the risk of concurrent currency devaluation. Periods of decline typically instigate currency devaluation, and as the currency loses its efficacy, society’s capacity to resist further decline dwindles.

Deprived of healthy money, society’s ability to coordinate and cooperate effectively diminishes. Gradually, societal declines may transform into an irreversible descent over generations, ultimately threatening its very existence.

Globalization proved to be a pivotal moment in the evolution of our modern economy. A global economy requires money that can be rapidly transported across borders without excessive costs, rendering gold impractical as a medium of exchange in both domestic and international trade. To accommodate the expanding worldwide economy, countries migrated from the gold standard to the fiat standard9 In 1971, the final link between gold and the dollar was severed, officially abandoning the gold standard[^10] in favor of a fiat standard.

Currency creation, i.e. currency debasement, may conjure an illusion of a golden era marked by rapid growth and abundance, but this façade comes at the expense of the general population’s wealth, the wealth of future generations, and society’s ability to coordinate and sustain functional institutions. The Roman Empire’s currency debasement fostered an appearance of territorial expansion; however, it was akin to stripping a tree of its heartwood, leaving only a brittle shell. Just as a tree cannot thrive without its heartwood, the denarius could not survive without its silver core. The same holds true for our current fiat currencies, which were originally a proxy for gold but abruptly lost their connection to it in 1971.

The collapse of a civilization, anchored to its economy’s failure, is intrinsically linked to the strength of its currency. When the denarius collapsed, Roman officials introduced currencies, but none gained widespread acceptance. Without a suitable replacement, the denarius gradually vanished, taking the entire Roman Empire with it.

The devaluation of the denarius to 0% silver marked a critical turning point when the decline of the Roman Empire became irreversible. Although, by this time, institutions were crumbling, living standards sharply deteriorating, and the population dwindling, the demise of the denarius triggered the empire’s economy’s final implosion, rendering recovery and resurgence impossible.

The once-magnificent Roman Empire succumbed to a singularity crisis. With the denarius no longer a viable tool to orchestrate society’s cooperation and coordination, Rome grew unable to solve new problems and introduce more complexity to advance as a society. Despite its past splendor, the Roman economy fragmented to a mere shadow of its former self.

By 476 CE, the empire had disintegrated. As the major economic power in the world, it sank to the depths of the ocean floor like a ship caught in a vortex, dragging every boat in its vicinity down with it and plunging the European continent into a period of intellectual, political, cultural, and financial darkness - the European Dark Ages.

Want to read the rest of this book? Click below.

Or buy it on Amazon

Footnotes

Footnotes

-

Author, The Collapse of Complex Societies. ↩

-

An institution is a complex societal structure established to serve a specific social purpose and has a set of standardized procedures, practices, and norms. Some examples of institutions include educational, political, financial, and religious organizations, as well as family, healthcare, media, legal systems, agriculture, and food systems. ↩

-

Throughout this book, “decline” to refers to the process leading up to collapse, and “collapse” signifies its completion. For instance, Rome experienced a decline over a period of approximately 500 years before ultimately collapsing in 476 CE. ↩

-

A resource is anything that can be leveraged to produce an economic good to grow the economy, including human beings, time, food, money, precious metals, building materials, medicine, weapons, knowledge, and more. ↩

-

A post-scarcity society represents an age of abundance, where automation has seamlessly taken over major societal functions, and an almost limitless source of energy is available to humanity. ↩

-

Alternatively, money can be defined in a somewhat drier but equally illuminating way, such as a shared immutable correct ledger, apex property, the most saleable good, or tokenized time. ↩

-

In the realm of fiat currency, the monetary system relies on the fickle trust of its users and the fragile stability of the issuing government. The state wields ultimate control over the currency’s issuance and distribution, possessing the power to create any amount of money with a mere push of a button. The vulnerability of fiat currency lies in its intangible nature, unbacked by any tangible assets and merely sustained by governmental decree, leaving it susceptible to depreciation. As the global economy expands, the allure of devaluing currency to meet the increasing demands of a complex world grows stronger. ↩